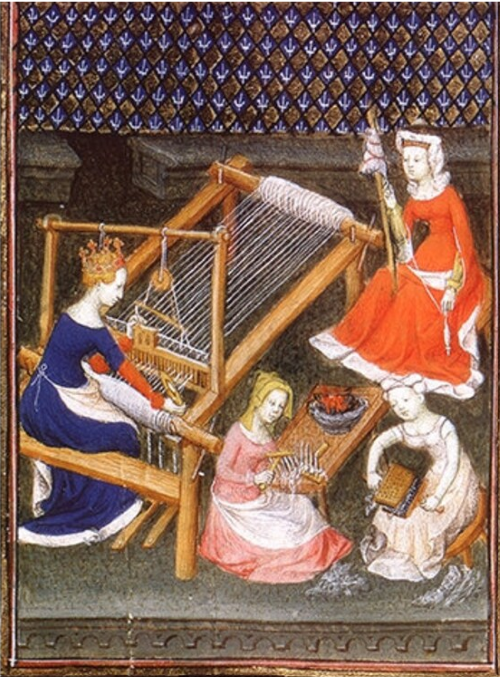

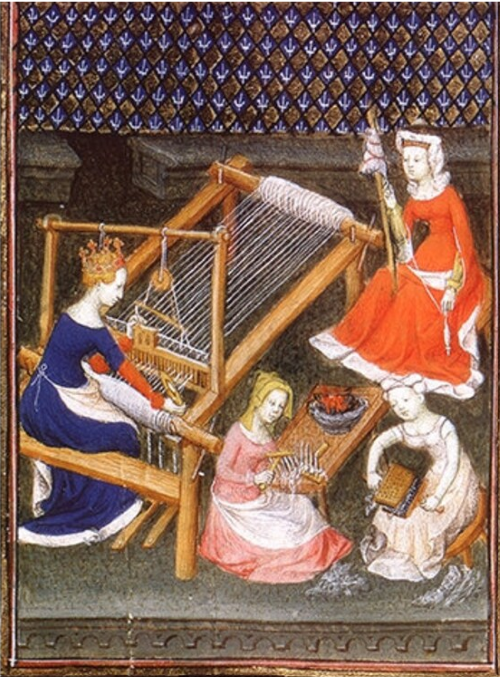

Women’s labor in the Medieval period was varied, but mostly consisted of low-skilled jobs such as prostitution, brewers, midwives, and hucksters. One of the most ubiquitous forms of labor was weaving. Many women could weave in their homes and make a small wage while their husbands also had jobs. Weaving as a skill was expected of women as an extension of their female household duties making it a common form of labor for many. However, toward the late Middle Ages, women weavers in London engaged in a specialized product: silk. Silk was considered a luxury good in Europe at the time, often purchased and worn by those of a higher socio-economic standing. In mainland Europe, several markets for silk had developed in France and Italy prior to the establishment of London silk workers. Since textile work was women’s work, female weavers in London had little issue transitioning to a different material.

Sylkewymmen or silk weavers began their work by turning raw silk into yarn and using the material to make products, such as clothes and accessories. Silk weaving was different from other women’s work because it was highly skilled and highly respected. Despite this, the sylkewymmen of London never formed a gild. By 1368, sylkewymmen were established enough to petition the mayor of London to protect their craft against competition. Several petitions were made to Parliament throughout the 15th century by sylkewymmen to protect their craft and art. Why didn’t they form a gild, historian Marian K. Dale asked in 1933 that historians Maryanne Kowaleski and Judith M. Bennett built upon a half-century later. Kowaleski and Bennett argue that gilds during this time were male-dominated. Women could participate in gilds as apprentices and wives of gild members, but their political power and benefits were significantly reduced compared to their male peers. The sylkewymmen of London formed a quasi-gild, in the sense many advocated and petitioned Parliament for special sanctions and protections, and the legacy of the trade passed between women.

While these women never formed a gild, their careers offered them opportunities for independence that they never would have experienced in other fields of labor. For example, sylkewymmen often traded with foreign merchants to acquire luxury silk to make special products. Many London sylkewymmen were not identified by their relation to men in records, as was typical of the era. This could signify their independence from men, even if married their trade’s respect afforded them similar consideration. London silk women were often patronized by nobility and those of high society.

The height of sylkewymmen’s prominence in London is brief in the historical record. As with many female-dominated labor sectors, like brewing, by the 16th century, men overtook them eventually edging them out. For sylkewymmen, it is especially discouraging because as men moved into the industry, they quickly formed a gild to protect their labor.